By Publisher Ray Carmen

It was the 1960s , the Jet Age was in full roar, and America wanted its own supersonic crown. Across the Atlantic, Britain and France were building the Concorde, a sleek white dart that promised to slash travel times and redefine global prestige. The United States, unwilling to be outshone, answered with a dream of its own: the Boeing 2707 , an aircraft so advanced it would have flown faster, higher, and farther than anything before it.

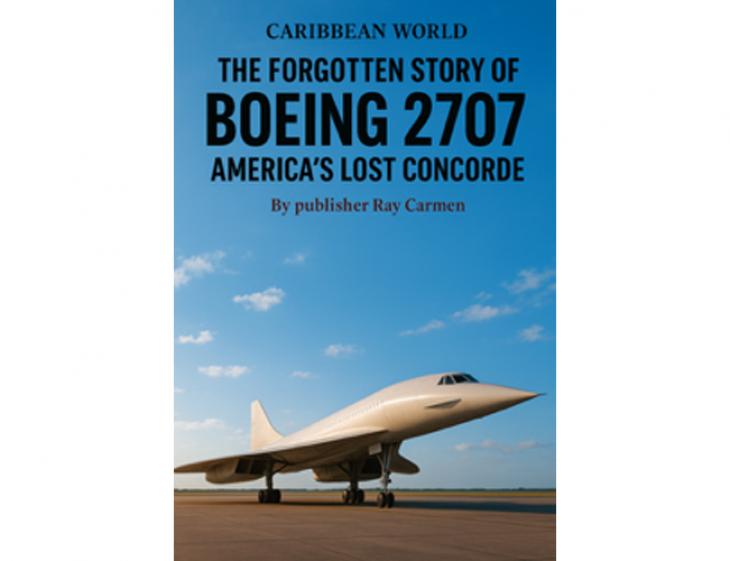

The 2707 was to be the world’s first supersonic airliner built at massive scale, reaching speeds of Mach 3 , nearly three times the speed of sound. With swing wings, titanium skin, and space-age design, it embodied America’s unshakeable confidence in engineering dominance. President Lyndon B. Johnson hailed it as the “flying symbol of the free world.”

But while the dream soared on paper, reality clipped its wings. Mounting costs, environmental concerns, and sonic boom protests turned the project into a political minefield. As the price tag exploded and airlines lost faith, Congress pulled the plug in 1971. The great American Concorde never left the hangar.

What remains today is a ghost of ambition , two unfinished prototypes, gathering dust in museums, silent witnesses to a time when the sky had no limits and dreams were measured in Mach numbers.

In the end, the Boeing 2707 became more than a cancelled aircraft; it became a symbol of a nation caught between innovation and hesitation , a reminder that sometimes, even the brightest dreams fall just short of takeoff.